Heraldic law

Scottish Heralds on horseback, 1685

The first work on heraldic law, ‘De Insigniis et Armiis’ (On Insignia and Arms) was written by Bartolo of Sassoferrato, professor of law at the University of Padua, in the 1350s.

From the earliest times of European heraldry, arms have passed by inheritance from father to sons (and daughters) and are strictly speaking the heritable property of the holder. A coat of arms may be borne by the original bearer’s legitimate lineal descendants, with the eldest heir using undifferentiated arms and the others with modifications (cadency) to express the difference and maintain uniqueness.

In some countries, such differences are not necessary in heraldic law, and the arms of the original armiger pass equally to all male descendants. In other countries it is only the senior heir who can bear the original arms. In Scotland, all arms must be granted or matriculated (registered) and differentiated from those of the original armiger, except where they pass to the eldest heir.

The practice of all descendants bearing undifferentiated inheritance in some countries has led to the unfortunate misconception – first encouraged by unprincipled printers and stationers in the 19th century and perpetuated by bucket-shop ‘Your Family Crest’ merchants today – that a coat of arms somehow belongs to everyone with the same surname, whether or not there is any real family relationship. ‘Family crests’ (which is wrong anyway, since the crest is only one part of a full armorial achievement) are sold to a gullible public. What they will probably get is a version of the arms of the chief of that name (which is, of course, the legal property of the current chief), or of the first person of that surname on the database – and which stands a good chance of being Irish or English,and with an inaccurate narrative. An armiger in Scotland has paid an exchequer tax on the arms and any impostor displaying falsely acquired arms risks legal prosecution.

However, as described in How does heraldry work?, a member of a family or clan may wear and display the crest within a strap and buckle, indicating familial allegiance to the armigerous owner.

Legally, it is the blazon (the word description) which is important, and which is inherited, rather than the design as such, so it can be thought of more as a patent than a logo. Hence, there may be differences in detail between depictions of arms – the exact size or placement of charges on the field, the number of claws of a dragon, the look of a fish or a castle.

Canon Dr Joe Morrow, Lord Lyon

The important difference between Scottish and English heraldic law is that in Scotland it is a matter of statute rather than civil law. Since a coat of arms may only be used if recorded in the Public Register of All Arms, approved by the Lord Lyon, no two individuals can bear the same arms at the same time, even by accident. To pretend to arms not so granted brings the matter under statute law and there may be proceedings in the Lyon Court, which is fully part of the Scots criminal justice system. Anyone who has stained-glass windows, dinner services, silver cutlery or anything else made carrying arms they do not legally possess, may find the whole lot confiscated and a fine imposed.

In England, the only legal recourse for someone who feels his or her arms have been usurped is to mount a civil action in the Court of Chivalry, which has not met in such a matter since the 1950s and is not an integrated part of the English judicial system.

The relevant Scottish laws, generally known as the Lyon King of Arms Acts, were passed in 1592, 1669, 1672 and 1867.These can all be consulted, in their original form or as amended, at www.legislation.gov.uk

The Lord Lyon is far more than just a recorder of arms and organiser of royal processions; he is also a senior judge in his own court, and a minister of state. In Scotland, arms are the individual, heritable property of one person and must be granted by the Lord Lyon King of Arms (www. lyon-court.com).

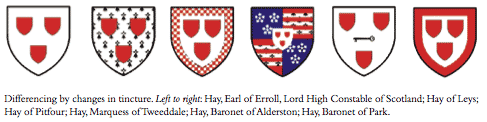

There is a convenient fiction in Scottish heraldry that everyone of the same surname is related. Everyone recognises that this is not so, but it does mean that new arms will reflect those of a previous armiger of that name. Anyone called Hay applying for arms will get some variant of the three escutcheons pictured. But this does not mean that anyone can simply adopt arms of someone with that surname.

The Lord Lyon, Lyon Court and Public Register

The Lyon Court and Lyon Office are located within New Register House in Edinburgh. The origins of the Lyon Court are lost in time, as are the earliest registers (if they ever existed in such a form). Many Scottish records certainly went to London with Edward I in the early 1300s and though much has been returned, some was not. Early records of arms in Scotland were regarded as more or less the personal property of the heralds and have been lost in fires or to the ravages of time, and through neglect.

However, armorials were made for private use.The earliest surviving armorial roll is probably the ‘Balliol Roll’, thought to be an English manuscript from the 1330s.The ‘Armorial de Gelré’ (1369–88), the ‘Armorial de Berry’, the ‘Armorial de l’Europe’ and the ‘Scots Roll’ (1455–58, since republished by the Heraldry Society of Scotland) came next. From the 1500s we have the ‘Forman-Workman Manuscript’ (probably a working book of a heraldic artist, and dating from about 1510), the ‘Register of Lord Lyon Sir David Lindsay of the Mount’ (1542), the ‘Hamilton Armorial’ (1561–64) and several others.

More Scottish parliamentary and other records were removed by Oliver Cromwell during the War of the Three Nations and many were lost at sea when being returned in 1661 aboard the ship Elizabeth of Burntisland on its way to Edinburgh. It is not known whether armorial records were among them. This led to a law passed in 1672 by the Scots Parliament, and administered by Scotland’s Lord Advocate, Sir George Mackenzie of Rosehaugh (c. 1638–91), by which the Public Register of All Armorial Bearings of Scotland was set up and the Lord Lyon enabled to oversee heraldic law from a central record. Registration was free for the first five years, but compulsory on pain of a fine. This worked, so the first volume records many classic Scottish arms.

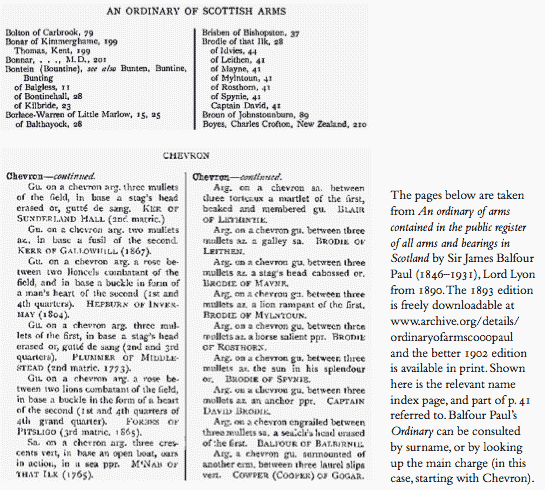

The Public Register is exactly that, and can be consulted for a fee or accessed via www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk with a fee for downloading each record. However, it is usually sufficient (and cheaper) to consult Balfour Paul’s ‘Ordinary of Arms’ and its supplement, which together list arms granted from 1672 to 1973 .

Can I have Scottish arms?

If you are Scots,or of Scots descent,and not living in a country where there is a heraldic authority (such as England, Ireland, South Africa or Canada), and if you are a ‘worthy and virtuous person’, arms are possible. There are three routes:

1. If you can prove that you are heir to someone who at some time properly matriculated a Scottish coat of arms, then you can petition the Lyon Court to matriculate these in your name;

2. If you have no armigerous direct forebears, you can petition for a new Grant of Arms;

3. If you live in, say, America and have no property in Scotland or residence there, it may be possible to petition for arms in the name and memory of a long-deceased Scottish ancestor, then establish a cadet matriculation.This is useful – and cheaper – when a number of members of a family want to achieve arms.

There is more to it than that, including considerations of ‘domicile’ (a tricky Scots legal concept), but full guidance is available at www.lyon-court.com and click on ‘applying for a coat of arms’. You will need to shows ‘proofs’, which means more than submitting a family tree and will involve getting legally certified copies of documents such as birth, marriage and death records, wills and testaments, charters and more besides. There are templates of the ‘prayer’ to the Lord Lyon on the site and it is not usually necessary to hire a lawyer.

The legal position over ownership of arms is more straightforward – arms belong to the person to whom they are granted and to the heirs of that person according to any limitations of the grant or of tailzie (entail). In England, the right to a coat of arms passes to all male descendants of the armiger, but in Scotland a coat of arms is incorporeal heritable property and so can only belong to one person at a time. This is why the younger children of an armiger have no direct right to inherit the arms (unless and until all elder branches die out) and why they must matriculate the arms with a difference.

Lyon has ultimate and full discretion as to what any coat of arms will look like, but is happy to take the petitioner’s wishes into consideration, subject to heraldic law, matters of taste and the surname concerned. Once devised and blazoned, the arms are painted onto vellum along with a recitation of personal and family history and the full blazon (see Introduction to Scottish Heraldry for the Letters Patent for the arms of the author’s father). Once recorded in the Lyon Register, these arms have the full protection of the laws of Scotland, and the armiger becomes one of Scotland’s ‘noblesse’ – not the same as ‘nobility’, which would indicate a peerage.

The fees payable are set by statute and currently (2011) range from £1,364 for a new grant of a shield alone, with or without a motto, to £3,754 for a new grant of a shield, crest, motto and supporters to a commercial organisation. Extra charges may be levied for additional painting work, postage and so on. There is an up-front fee of £200 on lodging the petition, the balance due when the arms and draft text are agreed. Payment is only by Sterling cheques payable to Lyon Clerk for HM Exchequer. Expect the process to take up to two years, and build in time and an additional budget for the required genealogical work.

The Court of the Lord Lyon can be contacted at: HM New Register House, Edinburgh EH1 3YT, and there is a full scale of fees at www.lyon-court.com/lordlyon.

See Achieving a Coat of Arms >>

The Royal Arms of Scotland

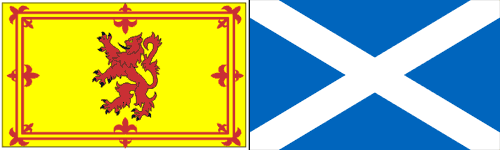

The simplest and therefore most dignified of all the royal arms, Scotland has Or a lion rampant Gules armed and langued Azure, all within a double tressure flory-counter-flory of the Second. It is said that these were first adopted by William I (the Lion), King of Scots 1165–1214.

The King of Scots, 15th-century – surcoat, tabard and horse trappings, all in the royal livery of Scotland.

They are also remarkable in showing an early form of differencing. Aedh, the eldest son of Malcolm III and Abbot of Dunkeld, was barred from taking the throne so his descendants, chiefs of clan Macduff, bear he simple Or a lion rampant Gules, while the kings descended from David I have the double tressure.There are other Scots arms bearing a lion rampant, often indicating a connection with one of the ancient royal houses of Scotland – Buchanan, Wallace and, of course, Lyon of Glamis (now the Earls of Strathmore & Kinghorne) are examples.

Despite being waved around at football matches, the lion rampant is not the flag of Scotland, and can only be used properly by the sovereign and certain great officers of state (including Lord Lyon and the First Minister). The Scottish flag is the white saltire on a blue field.

Lion Rampant (left) and Saltire (right)

Also see our ‘What you can and can’t wear and display section >>

This information was kindly supplied by Dr Bruce Durie:

This information was kindly supplied by Dr Bruce Durie:

Dr. Bruce Durie BSc (Hons) PhD OMLJ FSAScot FCollT FIGRS FHEA

Genealogist, Author, Broadcaster, Lecturer

Shennachie to the Chief of Durie

Shennachie to COSCA

Honorary Fellow, University of Strathclyde

Member, Académie Internationale de Généalogie

E: bruce@durie.scot

W: www.brucedurie.co.uk